The Triple Crown: An Account of the Papal Conclaves

by Valérie Pirie

< Prev T of C

... XVIIth Century

XVIIIth Century

XIXth Century

Concl. Ch.

Biblio

Next >

CONCLUDING CHAPTER

LEO XIII AND HIS SUCCESSORS

SINCE the conclave which raised Pius VI to the Holy See in 1775 no papal election had taken place in

the Vatican. All the paraphernalia employed for the erection of the cubicles had remained stored away in

the attics of the Quirinal, nor would it really have been possible to make use of it in the older building,

where the cells had to be contrived on quite different lines. Five hundred workmen—masons, carpenters,

joiners and upholsterers—under the supervision of an architect, worked feverishly night and day to have

everything in readiness by February 18th, on which date the Sacred College was due to enter the

conclave. The innumerable parasitic idlers who nested in the Vatican were pressed into service, being

made to hold the workmen's lanterns, to shift furniture and run errands. The venerable edifice echoed

with the sound of sawing, hammering, knocking and shouting, the hustle and pandemonium increasing in

intensity as the final day drew near.

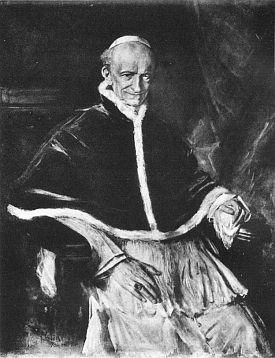

| LEO XIII

From the painting by Lenbach, Pinakothek, Munich

|

|

|

Meanwhile the busybodies shook their heads and hinted at mysterious dangers likely to encompass the

assembly if it held its sittings in Rome. Various places of safety were suggested in Austria, France or

Spain, and Cardinal Manning, who considered himself the leader of the ultramontanes, urged his

colleagues to migrate to Malta, where they would be under the protection of the British flag. At first the

majority of the suffragists, influenced by the genuine or assumed pessimism of the wiseacres, were in

favour of setting out at once for foreign parts; but as time slipped by and no official invitations reached

the Sacred College from any of the European Powers, the cardinals began to doubt the wisdom and even

the feasibility of the plan. The Catholic monarchs on whose hospitality they had counted as a matter of

course not only evinced no desire whatever to welcome them within their dominions, but went so far as

to advise them strongly to remain in Rome. Most of the European cabinets had urgent problems [p. 338]

to deal with just then in various parts of the world and were only mildly concerned with the papal

election. Moreover, being on good terms with the Italian Government, they were naturally disinclined to

meddle in the matter. So strongly did the British Government feel on the subject that Sir Augustus Paget,

the English Ambassador to the Quirinal, was instructed to inform the Italian Foreign Secretary that

Cardinal Manning's proposal to hold the conclave in Malta had been made entirely on that prelate's own

initiative.

In view of the ostensible aloofness of the Powers and of the difficulty experienced in selecting a suitable

locality abroad, the cardinals at last decided to hold the conclave in Rome. This determination had not

been arrived at without endless arguments and deliberations during which such absurd suggestions were

put forward that Cardinal Ferrieri, losing patience one day, exclaimed sarcastically: "Why not in a

balloon, then?" The dread of the older prelates for the trials and hardships of a long journey had proved a

great deterrent, and the enormous expenditure such a move would have entailed also weighed heavily in

the balance. On the other hand, the Italian Government had guaranteed the security of the conclavists,

and their complete immunity from any form of interference, so it was becoming increasingly difficult to

keep up the fiction of the perils which beset them. The Sacred College therefore adopted the only

sensible course open to it, and thus the strenuous labours of the Roman workmen were not wasted.

When the prelates entered the Vatican on February 19th, 1878, everything was in readiness for their

reception. No trouble or expense had been spared to minimise the discomforts of their claustration. A

profusion of gas-jets sizzled round every corner dispelling the winter gloom, electric bells had been

installed in all the cubicles, and the cubicles themselves been considerably enlarged. They were no

longer the box-like contraptions of yore but real rooms in many cases, and where that had not been

possible decent-sized cells had been contrived. Communal kitchens established within the precincts of

the conclave itself precluded the necessity of the cardinals' meals being brought from their residences,

thus obviating the confusion and disturbance at the wickets inevitable under the old system. All their

Eminences had agreed to this arrangement with the exception of Cardinal Hohenlohe, who detested

macaroni, and being something [p. 339] of a gourmet insisted on being supplied with food cooked in his

own palace.

Owing to the increased facilities for locomotion sixty-two prelates, almost the largest number ever

gathered together for a papal election, answered the Camerlingo's summons to Rome. Under Pius IX's

long pontificate the Sacred College had been virtually renewed, only four of the cardinals having ever

attended a conclave before; and in spite of the improvements made in the accommodation, many of the

inmates complained bitterly of the discomfort of their quarters. Cardinal de Falloux declared that the

smell in his room was intolerable and that he would sleep in the passage as long as the conclave lasted. If

he did so, it was only for a couple of nights, as the whole proceedings were over in thirty-six hours; in

fact, had it not been for the inexperience of the suffragists, the business would have been concluded even

sooner, but they invalidated the first scrutinies by committing every sort of blunder imaginable.

The loss of the temporal power, and the pose of voluntary captivity bequeathed to his successor by Pius

IX, had considerably reduced the number of aspirants to the Sovereign Pontificate, and several openly

declared their unwillingness to shoulder a burden for which there were now no material compensations.

The total absence of simony and of political intrigues resulted in the suffragists arriving at a rapid and

satisfactory conclusion, there being now no obstacle to their choosing and electing the man they

considered the most worthy to wear the triple crown.

Practically all the cardinals entered the conclave with their minds already made up as to whom they

would give their votes. The majority were in favour of Pecci, the Camerlingo, who had shown so much

competence and decision during his short period of administration. He was generally credited with

possessing the very qualities needed at this juncture to make the perfect Pope. His morality, godliness,

rectitude and ability were unquestioned. A long and successful diplomatic career had particularly fitted

him for the task of establishing friendly relations with the foreign Powers, some of which had been on

distinctly bad terms with Pius IX. Pecci was in every way the exact antithesis of the late Pontiff, being as

quiet and reserved as Pius had been impulsive and exuberant; as studious, erudite and witty as the other

had been shallow, uncultured and [p. 340] jocular. Physically also he contrasted strikingly with the late

Pope, being tall and emaciated, with a long nose and a rare, subtle smile. Pius had frankly disliked him

and Antonelli no less frankly detested him, so that several of the cardinals who owed their hats to the late

Secretary of State opposed Pecci out of loyalty to their benefactor's memory. Their candidate, Franchi,

however, realising the futility of battling against overwhelming odds, advised his adherents to vote for

Pecci and himself led a movement to elect his rival by adoration.

After showing great reluctance to accept the dignity thrust upon him, Pecci was at last induced to yield to

his colleagues' solicitations and chose the name of Leo XIII, his election, which had been confidently

anticipated, being generally well received.

Besides his moral qualifications the new Pontiff's dignity of bearing, his distinguished appearance, his

emaciation and perfect poise made him the ideal representative of his exalted spiritual office. He had

shown remarkable proficiency and determination while delegate at Benevento in handling the turbulent

nobility of the district, and had succeeded in stamping out brigandage in face of systematic obstruction

on the part of local magnates and even of his fellow-churchmen. A great deal was expected of his good

sense and self-reliance where the relations to be established between the Holy See and the Quirinal were

concerned; but these hopes were doomed to disappointment. He adhered to his predecessor's policy of

claustration and rigid hostility towards the Italian Government. He may in a measure have been

influenced to adopt this line of conduct by the ultramontane atmosphere of the Vatican; but considering

his strength of mind it is more likely that he acted on his own initiative in accordance with his

fundamentally conservative proclivities.

Leo XIII belonged to a generation which considered the temporal power as inherent in the Roman

Pontificate; a generation which had witnessed the repeated triumph of the Holy See over a series of

vicissitudes. He would therefore consider that in acquiescing with what had come to pass, he might be

jeopardising whatever chances the future might hold of a restoration of the temporal power.

Consequently he could not but adopt the pose of a protesting victim, which was to become the traditional

attitude of the Holy See until the Treaty of the Lateran in 1929 rang down the curtain [p. 341] on the

protracted monodrama. It must also be borne in mind that at the consistory held immediately after Pius

IX's death all the cardinals had sworn "to defend the rights, prerogatives and possessions of the temporal

power of the Holy See usque ad effusionem sanguinis" and Leo was not the type of man to disregard an

oath.

The sedentary existence which the Pope was henceforth to lead and which he believed would prove so

injurious to his health, seemed on the contrary to suit his constitution most admirably, for although his

features grew more and more diaphanous and his frame gaunter and yet more gaunt, he lived to the great

age of ninety-three without showing any traces of senility. Leo XIII loved solitude, meditation and study;

he read and wrote incessantly (for he was a great scholar and even something of a poet), but most of his

time was devoted to religious compositions.

The Pontiff showed no conventional reverence for the late régime. He immediately set about clearing the

Vatican of the superfluous officials and their satellites who overran the palace. All women without

exception were requested to leave the premises and the castrati were pensioned off, their mellifluous

voices never again to be heard in the papal choirs. He put an end to all wasteful expenditure and reduced

certain bonuses allowed to the Swiss Guards. This last measure resulted in a serious mutiny breaking out

among the soldiery, which, however, was adequately dealt with.

In the guidance of his foreign flocks the Pope's policy was clearly that of rendering unto Caesar that

which is due to Caesar; he strove consistently to bring about a good understanding between Catholics of

all nationalities and their several governments by preaching tolerance and submission, an attitude, by the

way, deeply resented by the French légitimistes and also by the Irish hotheads. He made friendly

overtures to Bismarck, with whom Pius IX had been at daggers drawn, and kept on excellent terms with

the whole world, excepting of course the Italian Government. The Quirinal certainly had some cause for

complaint. Whenever the Pope could put a spoke in its wheel he never failed to do so; as for instance by

helping France to consolidate her position in Tunis and Northern Africa generally, which he effected by

granting her missionaries special facilities, to the detriment of Italian colonial expansion.

Under Leo XIII's pontificate the Holy See developed an occult [p. 342] influence of immense magnitude

which it is now unlikely ever to relinquish. The "full, free and independent exercise of spiritual power"

which Papacy purported to have lost with its temporal possessions was exactly what it had acquired; and

politically the Pope of Rome as infallible director of four hundred million consciences must always be a

power to reckon with. Therein lies his supremacy, not in the temporal sovereignty over a paltry four

million disaffected subjects which he once enjoyed.

Everywhere in Italy the deep-rooted prejudice against the Holy See persisted unabated, and indeed it is

not to be wondered at. The collections for Peter's Pence in 1891, the returns for which are given by

Witte, show a sum of only 15,000 lire subscribed by Italy—less even than the amount sent to the Holy

Father from poverty-stricken Ireland—as against four million francs contributed by France.

Modern conclaves are all held on the pattern of the one which elected Leo XIII. They are rapid, business-like and as free from outside interference and internal intrigues as is compatible with ordinary human

nature. Shorn of its mundane splendour, the Sovereign Pontificate remains the supreme dignity to which

the ecclesiastical career can lead and therefore desirable withal. Since the complication of Italian politics

has disappeared and the Treaty of the Lateran has freed the Holy See from all dependence and

equivocations, there seems no reason why future popes should be chosen exclusively among cardinals of

Italian nationality and why the Vatican should not become as cosmopolitan as the Church is Universal.

The right of veto has also vanished with all the obsolete prerogatives of the past. It was claimed for the

last time in 1903, when Austria made use of it against Cardinal Rampolla during the conclave which

followed Leo XIII's death. This anachronistic intervention on the part of His Apostolic Majesty surprised

everybody and roused the greatest indignation among the members of the Sacred College, in

consequence of which the new Pope, Pius X, made the abolition of the privilege of veto the subject of his

first official pronouncement. Of those great Catholic monarchies self-styled pillars of the Church of

Rome not one now remains. Their Most Christian, Apostolic, Catholic and Faithful Majesties have all

vanished, and their democratic successors would feel as embarrassed at brandishing a veto as at handling

a sceptre. As a matter of fact Rampolla would never have [p. 343] mustered the sufficient majority of

votes to secure his election, and he was the gainer by Austria's premature gesture of malevolence

towards him, inasmuch as it gave his defeat the appearance of having been brought about by a

treacherous knock-out blow, when in reality his failure was inevitable; the world at large being still convinced that had it not been for the Austrian veto Rampolla would certainly have been elected Pope.

Cardinal Matthieu, an ebullient and irrepressible Frenchman and a devoted adherent of Rampolla's,

wrote an account of this conclave which was published in the Revue des Deux Mondes. The article,

written in a distinctly satirical vein, was considered in Rome an unpardonable indiscretion. Matthieu was

the stormy petrel of the Sacred College; he was proud of his plebeian origin and democratic principles

and constantly ruffled his colleagues' feelings by contravening the rules of prelatic etiquette, covering

them with confusion by his pertinent sallies and general outspokenness. He was severely reprimanded by

Pius X for his literary transgression, and every precautionary measure was taken to prevent the

recurrence of such a breach of confidence, which would in future entail most severe penalties. The

strictest secrecy is therefore observed in connection with contemporary conclaves, which, truth to tell,

are probably of little interest to any but those directly concerned in them.

And now that a satisfactory compromise has been reached between the Church of Rome and the Italian

Government, the fictitious captivity of the Popes is a thing of the past. The Vatican City is an independent

albeit diminutive State; Christ's Vicar is no man's subject, he is free of all political control and

of all foreign patronage. His Lilliputian realm confers on him the status and privileges of temporal

sovereignty without its burdens and responsibilities. At what period of history has the Roman Pontiff

enjoyed such absolute moral and material emancipation from all earthly control, such universal

deference and such unchallenged authority over his world-wide flock as he does under the present

circumstances? It is indeed well that the old order of things should be abolished, and that the scandalous

abuses of bygone days should have disappeared for ever with the system from which they sprang. The

devastating and pernicious system which the great Italian poet has branded in a magnificent [p. 344]

canto of his Inferno, on the last lines of which we will most fittingly close this book:

|

Ahi! Constantin, di quanto mal fu matre,

Non la tua conversion, ma quella dote

Che da te prese il primo ricco patre!

Ah! Constantine! To how much ill gave birth,

Not thy conversion, but that dower

Which the first rich Father took from thee!

|

THE END

< Prev T of C

... XVIIth Century

XVIIIth Century

XIXth Century

Concl. Ch.

Biblio

Next >

|