| Pickle Publishing | Pope Innocent X | Research Papers |

Return to https://www.pickle-publishing.com/papers/triple-crown-innocent-x.htm.

The Triple Crown: An Account of the Papal Conclaves

< Prev T of C ... XVth Century XVIth Century XVIIth Century XVIIIth Century XIXth Century ... Next >

Leo XI Paul V Gregory XV Urban VIII Innocent X Alexander VII Clement IX Clement X Innocent XI Alexander VIII Innocent XII

INNOCENT X (PAMFILI)

1644—1655

|

|

The Spanish candidate, Pamfili, was also a striking personality. [p. 166] His private life was not above suspicion like Sacchetti's, as he was known to be slavishly devoted to his widowed sister-in-law, Donna Olympia Pamfili, who for many years now had held him in thraldom; but Roman morals were lax and this long-standing attachment was readily condoned.

Pamfili was silent, reserved and exquisitely courteous. He was certainly not handsome with his bulbous nose, small close-set eyes and thin straggly beard; but his bearing was distinguished and pleasing.

The conclave had been assembled for three weeks before the first scrutiny took place, so busy were all the electors with their intrigues and financial transactions. Antonio Barberini was distributing abbeys and benefices and granting life annuities with a lavish hand, for besides his own vast wealth and possessions he disposed of the large sums of ready money which were pouring in from France.

Heiresses were being bartered against bishoprics and other dignities, a Gaëtano who had a splendid dowry playing an important part in the proceedings. The new Spanish Ambassador's arrival gave a renewed impetus to the bargaining as he made his appearance in a perfect blaze of Oriental splendour, having, he announced, sufficient doubloons in his coffer to buy up the whole conclave. He also had a couple of opulent princesses to dispose of in holy wedlock and fine estates to bestow in the kingdom of Naples. His first move, a very wise one, was to pay Cardinal de Medici's debts, which amounted to 150,000 crowns.

For practically a century now papal interregnums had lost their character of lawless brigandage and become a period of merrymaking and carnival masquerades. But while the conclave sat in August 1644 Rome wore no such festive aspect. The Duke of Parma's troops were known to be advancing on the city, and armed bands, levied, it was rumoured, by the Barberini, filled the streets with a martial tumult that could be heard even from the Vatican. The situation was certainly disquieting and the Sacred College began to feel the pressure of circumstances, so on August 29th the voting began in real earnest. Sacchetti's name was put forward by Antonio Barberini, but the result of the scrutiny was disappointing; nor did Francis obtain much better results with Pamfili on the following day.

Foreseeing the dangers of a protracted conclave, the two brothers now sought for means of winning one another over without loss of patronage and security. Antonio made the first move through the agency of M. de St. Chaumont, the French Ambassador. The offered terms were so advantageous that the affair would certainly have been concluded had it not been for the Frenchman's greed. Ten thousand doubloons and the bishopric of Avignon for one of his relations had been agreed upon as his private commission on the transaction, but when the compact was submitted to the brothers for signature, Antonio found that the sum now claimed by St. Chaumont was 20,000 doubloons to be paid immediately in cash or jewels of corresponding value. He was so enraged by this extortionate demand that he broke off all negotiations, much to the French Ambassador's surprise and discomfiture.

It was now Francis Barberini's turn to come forward with proposals from the Spanish party; they were substantial and satisfactory; for Pamfili was not only Philip IV's nominee but he was also acceptable to the Italian party, and in their name as well as in the King of Spain's he guaranteed the safety of the Barberini, giving his solemn promise to protect them from all attacks and reprisals and to obtain for them the Spanish Monarch's patronage. Evidently the dramatic history of the Caraffa did not in any way damp the optimism of the Barberini, for as soon as Pamfili had signed and sealed the document they repaired without demur to Medici's cell. Colonna's party was summoned to a conference and a general agreement reached without difficulty. The next morning Pamfili was proclaimed Pope under the name of Innocent X.

Mazarin was more than displeased both with Antonio Barberini and St. Chaumont. The Cardinal threw all the blame on the Ambassador for having ruined their schemes through his cupidity. St. Chaumont, on the other hand, denied ever having made the demand and accused Barberini of having had the clause inserted without his knowledge so as to have an excuse for going over to Spain. Whatever the truth of the story and whatever Mazarin may have thought of them both, he evidently considered it advisable to remain on good terms with the Barberini. The Ambassador was recalled and France continued to extend her patronage to the late Cardinal-Nephews.

It was soon apparent that they would need all the protection they [p. 169] could obtain as, in spite of all his promises, the Pope prepared to call the brothers to account for their depredations and delinquencies. There was certainly an immense outcry against them, but had they then and there offered Donna Olympia a sufficiently substantial bribe there is no doubt that proceedings would not have been taken against them; but they hated parting with money and thought that, by affixing the arms of France over the doors of their palaces and paying a band of mercenaries to defend them, they would escape retribution. Their enemies, however, were too powerful and too numerous; and before long they realised their mistake and fled to France. All their property in the Papal States was confiscated, and they remained in exile till they had gathered together sufficient resources to purchase their pardon from Donna Olympia, thus ending where they should have begun.

The elevation of Cardinal Pamfili to the Holy See pleased all parties but the French. He was a devoted partisan of Spain, a friend of the Medici, was related by blood to many illustrious Italian houses, had aroused no enmities and was seventy-two years old. Innocent X had great qualities: a kindly, peaceable disposition, frugal habits and—strange as it may seem in view of his treatment of the Barberini—a strong sense of justice. He disliked any form of oppression; relieved his subjects from much of the heavy burden of taxation laid upon them by his predecessors; constrained the nobles to pay their debts and considerably reduced the Vatican expenses. His diplomatic experiences in various European courts had taught him the value of reticence. He spoke little, was cautious and urbane.

For a short time all went well. Donna Olympia ruled the Papal States without contest, filling to all intents and purposes the office of cardinal-nephew. She received the ambassadors, treated with foreign Powers; no honours were granted or favours obtained but through her goodwill. Had it not been for her insatiable cupidity, matters might not have been so bad, as she was a remarkably competent, shrewd woman, and fully as well qualified to handle the reins of government as the average cardinal padrone. She had thought it advisable at first to have a nominal cardinal-nephew, and Innocent had invested her stepson with the office. But the chance of a brilliant match having come his way, Donna Olympia decided to dispense with the figurehead and marry him off to the rich heiress. Camillo [p. 169] Pamfili may have been a cypher, but his beautiful spoiled young bride certainly was not. She immediately entered into competition with her mother-in-law to capture the Pope's affections and undermine the older woman's influence. A perfect tornado of quarrels and hysterical tantrums now swept the Vatican, and the peace-loving, meditative Pontiff lived in a turmoil of shrill recriminations, vainly striving to restore harmony in the family circle.

|

In his foreign policy Innocent was consistently devoted to Spanish interests. It is said that at the time of the Neapolitan rising led by Masaniello the people offered him their allegiance; but he would have no dealings with Philip's rebellious subjects.

Towards France he was openly inimical. He condemned the five propositions of the Jansenists without, according to Voltaire, even troubling to read them, though that is unlikely. He gave the hat to Retz, who had been exiled from France, merely, it was said, to annoy Mazarin, who hated him. He protested, as was to be expected, against the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 which ended the Thirty Years' War by giving official recognition to the Reformation.

With all the Italian States he remained on friendly terms, with the exception of Parma, who had incited the inhabitants of Castro to murder their bishop. These he punished ruthlessly, Castro being razed to the ground. On the site where that unfortunate city had stood he caused a column to be erected bearing the inscription: "Qui fù Castro". Those were not merciful times.

Gout caused Innocent such intense sufferings that he was reduced during his latter years to leading an invalid's life, and his end was a sad and lonely one. His entourage shamelessly deserted him and his body lay unattended and unhonoured. All the customary ceremonial and tokens of respect were dispensed with; his family refused to bear [p. 170] the cost of his funeral, Donna Olympia declaring that she was only "a poor widow" and could not even afford the expense of a coffin. At last a humble canon of St. Peter's, outraged at such miserly callousness, himself paid for a pauper's coffin in which to bury the mighty Pontiff.

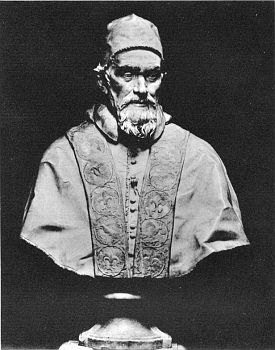

Two geniuses, Velazquez and Bernini, both at the height of their artistry, have left us contemporaneous portraits of Innocent X. They were both profound psychologists and uncannily proficient, the one with his brush and the other with his chisel, at rendering the personality of their sitters.

Bernini's bust of the Pontiff absolutely conforms to what is known of his character. The eyes have a look of benevolent abstraction; the line of the mouth expresses tolerant scepticism; the shoulders sag as though weighed down by an overwhelming lassitude; an indefinable suggestion of suffering broods over the marble presentment which the sculptor has endowed with such astounding realism.

Not so does Velazquez depict Innocent X. There is no sagging here; the attitude is firm and erect. Did the mild old man really harbour somewhere in the depths of his subconsciousness that streak of malevolent arrogance which exudes from every pore of the repellent features of this saturnine countenance? How can one reconcile these two portraits—both of them immortal masterpieces? Is it a case of dual personality? Perhaps. Yet one cannot help thinking that Bernini knew the Pontiff best. The artist was a familiar of the Vatican; Innocent would have sat quite naturally for him, relaxed and self-revealing. But on the famous Spanish genius he may have wished to make a more stately and conventional impression, an impression more in keeping with his exalted dignity. He may have purposely adopted the attitude which he thought would be expected of him by one used to the haughty, forbidding phantoms which peopled the sinister shadows of the Escorial.

Leo XI Paul V Gregory XV Urban VIII Innocent X Alexander VII Clement IX Clement X Innocent XI Alexander VIII Innocent XII

< Prev T of C ... XVth Century XVIth Century XVIIth Century XVIIIth Century XIXth Century ... Next >

© 2005

Pickle Publishing